Murder at Roaringwater – David McCullough on a shocking true tale

Updated / Tuesday, 29 Jun 2021 15:00

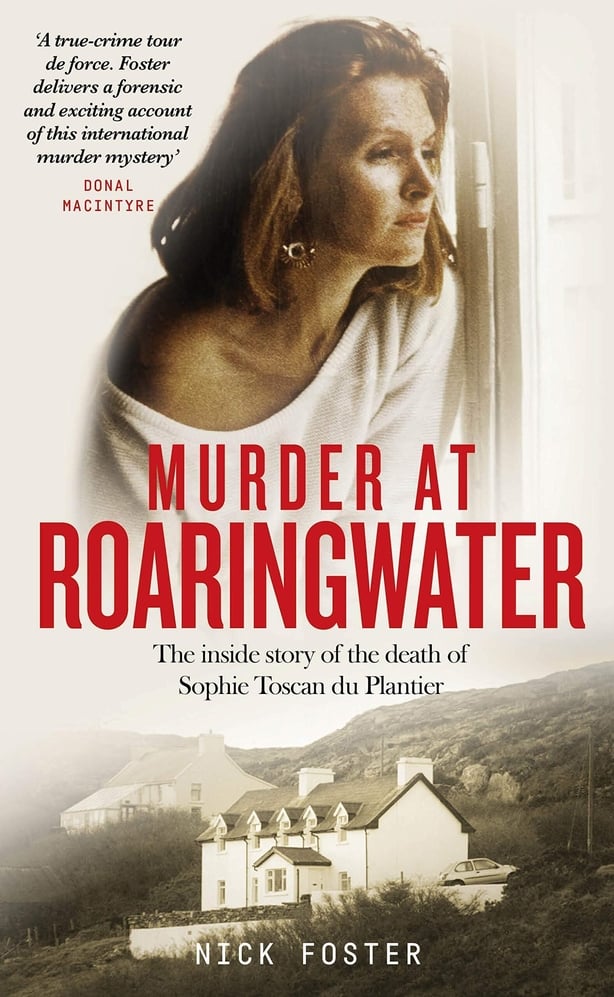

This is a well-written book, with much detail about the shocking 1996 murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier in west Cork, though some readers may wonder if it adds much to their knowledge of the case.

Central to the narrative is a guilty conscience.

That conscience does not, however, belong to Ian Bailey, the former journalist convicted in his absence of the murder by a French court two years ago.

Instead, it is the author of the book, Nick Foster, who is troubled by scruples.

Over the course of six years investigating the murder, Foster struck up a relationship with Bailey, who denies murdering Madame Toscan du Plantier: “I have got to know him personally, eaten at his kitchen table, run errands with him, gone on drives in the Irish countryside, and have even passed him the occasional €50 note to keep him talking… we bonded – sort of.”

Foster initially believed that Bailey was the victim of a miscarriage of justice, and hoped to be able to prove this. The story he would write, he thought, would be “about a David… taking on a Goliath, which was the entire machinery of a western European state.”

It was not surprising, then, that Bailey took to Foster, warmly referring to him as a ‘supporter’ – a label with which Foster became increasingly uneasy as time passed and his belief in Bailey’s innocence was shaken.

Because he needed access to Bailey, he felt unable to confront him, even when he knew Bailey was attempting to mislead him: “I knew that if I challenged Bailey… I wouldn’t be able to come back, his door… would be shut forever. No more contact, no more questions… That was what decided it for me: I was playing the longest of games.”

The case is a difficult one – Foster compares it to a set of Russian nesting dolls, with “each doll… coated with the dust of time”. But, as he points out, a degree of distance can be an advantage when trying to solve a problem. A fresh set of eyes on the evidence might catch an important point that has been missed.

Foster certainly offers new perspectives, some of them important, some of them not. The final clincher, for him, might not seem quite so definitive to others.

He records that Sophie had visited India some years before her death, and had written extensively in her journal about the trip, highlighting in particular a religious ceremony relating to the Hindu goddess Kali.

Reading witness statements, Foster comes across the evidence of French journalist Caroline Mangez, who interviewed Bailey shortly after the murder. In the course of this interview, Mangez reported that Bailey had spoken about Kali – the same goddess Sophie was so interested in.

This, Foster believes, had to be more than a coincidence – in fact, he claims it must mean that Bailey had in fact met Sophie Toscan du Plantier, which he had always denied: “I cannot believe that Bailey’s reference to Kali… came from anyone but Sophie – the odds of a strange coincidence are remote…”

Of course, as evidence goes, this is rather thin – it would hardly stand up in court. But for Foster, it is enough. “I offer no proof, no evidence beyond reasonable doubt. But I have a deep-seated conviction…”

This tees up the conclusion of the book – a rather melodramatic phone conversation in which Foster (by his own account) finally confronts Bailey with his “deep-seated conviction”. In a fittingly inconclusive end to the conversation, and the book, Bailey hangs up on him.

Which brings us back to Foster’s guilty conscience. Were the six years he spent cultivating Bailey worth it? Did the end justify the means?

In the introduction to this book, Foster relates a conversation he had with his two young sons. He asks them whether one should ever “be a bit false to somebody to find out a bigger truth”. The boys say no. Foster agrees – up to a point. This is the general rule, he says, but “sometimes you are compelled to make exceptions”.

The pity is that all the time he invested in convincing Ian Bailey that he was a ‘supporter’, all the lengthy conversations, all the confrontations he avoided, have not produced a more convincing and definitive “bigger truth” about this monstrous crime.

Murder at Roaringwater by Nick Foster (published by Mirror Books) is out now.