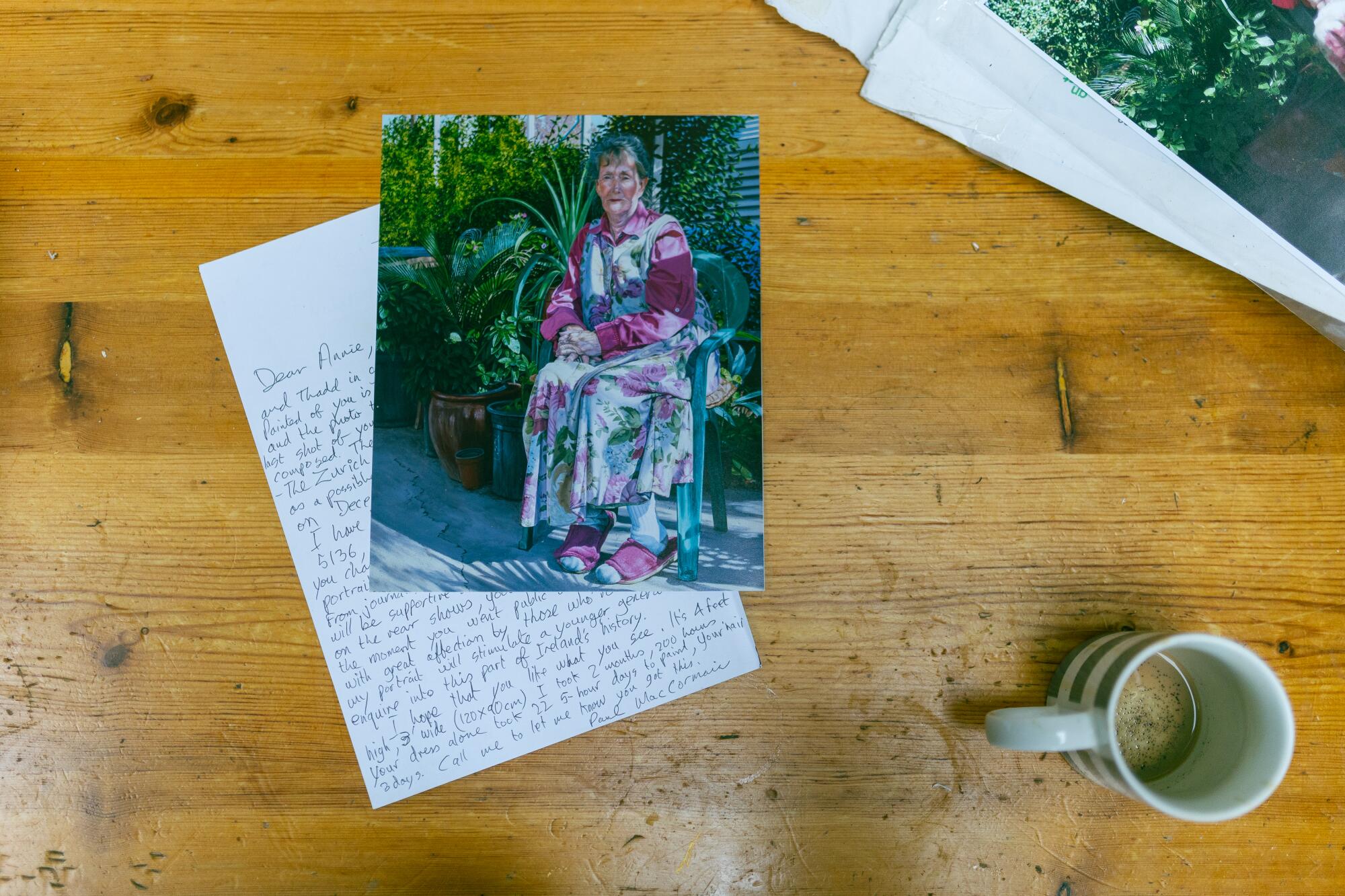

Hanging from a wall in the National Gallery of Ireland is a photorealistic portrait of a stoic, gray-haired woman wearing a fuchsia shirt and slippers with a dress adorned with fuchsia flowers.

She sits in a green plastic chair on a cracked-stone porch outside a mobile home in Riverside, with palm and orange trees in the background and a pale blue sky above.

It’s a serene Southern California scene in the halls of Dublin.

But who is this woman whose portrait was installed at the gallery in December, next to a photograph of legendary Irish singer Sinéad O’Connor? Her name is Annie Murphy, a woman unknown by almost all of her neighbors and described by her own son as “penniless.”

Yet thousands of miles away, across the Atlantic Ocean, Annie Murphy is a household name, her story a turning point in the country’s history. Three decades ago, she took on the Catholic Church when she revealed the affair she’d had with a celebrated Irish bishop — and the son he’d fathered.

Her incendiary story touched off heated debates in Ireland in an era long before #MeToo and before allegations of sexual impropriety against the church were commonplace.

“In terms of the shock it had on the Irish psyche, it was almost like the JFK assassination,” said John Cunningham, a history professor at the University of Galway.

The shock was triggered, in part, by her explicit memoir, which revealed the bishop’s secret and recounted their first kiss.

“What stunned me was the realization that he had done this before,” she wrote. “No one could kiss like that without practice.”

The story goes like this: Murphy was 25 and mid-divorce after an unhappy marriage and a miscarriage when she flew to Ireland to start fresh.

She was picked up at the airport by the then-bishop of Kerry, Eamonn Casey, who was her second cousin once removed. Murphy, an American from Connecticut, went to live at the bishop’s oceanfront home, called the Red Cliff House, in County Kerry.

No one could kiss like that without practice.

— Annie Murphy, on Bishop Eamonn Casey

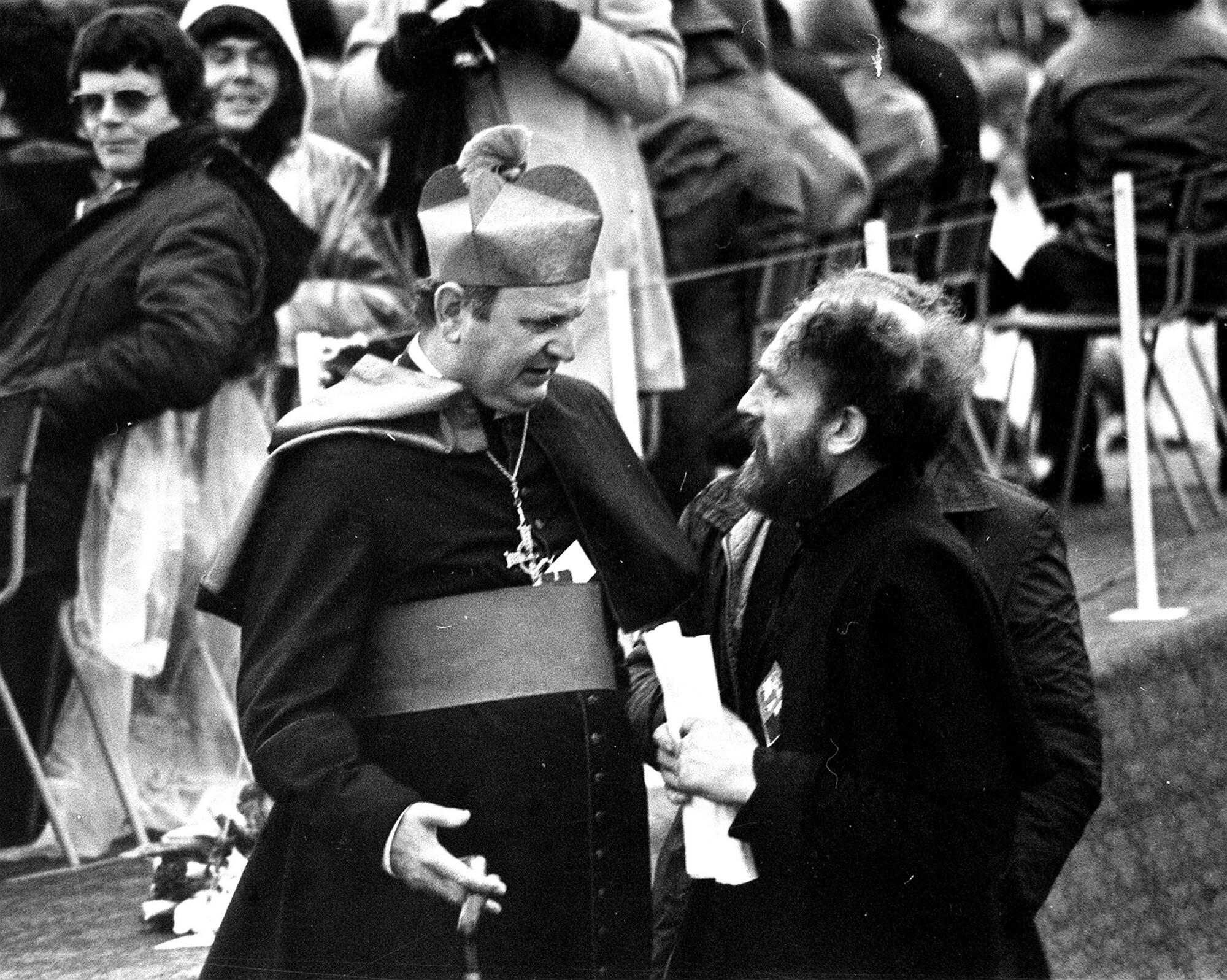

Casey was an influential clergyman, outspoken and jocular, as comfortable holding forth on political issues as he was on the pastoral needs of parishes under his purview. Whether campaigning to end poverty in Ireland or refusing to meet with President Reagan over Reagan’s policies in Central America, Casey often made headlines in Ireland and abroad.

He also was known for his indulgence in fine wines, expensive foods, travel abroad and fast cars that he could whip around his diocese at breakneck speeds. His speeding was so well known it inspired folk songs about the danger Casey-driven cars posed to Kerry sheep dogs. He even once picked up a ticket in London for drunk driving.

He was a captivating speaker and a forceful presence.

“His smile was enchanting, the feel of his hand warm and gentle,” Murphy wrote in her memoir. “This was for me the strangest thing in an already strange existence. … He certainly had charm.”

She fell in love with the bishop nearly immediately after arriving in Ireland in 1973. Casey, 21 years her senior at age 46, was equally smitten with the young woman he had welcomed into his home.

In her book, Murphy recounted their first kiss, when the bishop slipped into her room late at night.

Murphy was tormented at the beginning of the relationship, fearing that Casey would give her up due to his religious calling. But Casey told her he’d confessed and would continue their relationship.

“If God were here, he would approve of what I am doing,” Casey told Murphy, according to her book.

Casey, who valued his reputation, told her they had to keep their relationship a secret, she wrote. Even if she wanted to scream their love from the rooftops, she couldn’t.

Everything started to change when she became pregnant. The bishop wanted her to put the baby up for adoption, but she decided to keep the child. Eighteen months after the affair started, it was over and she moved back to the United States with her infant son, christened Peter, in 1974.

For the next nearly two decades, Casey made covert payments to Murphy to support their son. But once Peter became a teen, she wanted Casey to play a larger role in the boy’s life. The bishop, who represented Galway and Kilmacduagh, refused to do so. In 1990, Murphy filed a paternity suit against Casey.

The last straw came in 1992, when Murphy’s romantic partner at the time, Arthur Pennell, confronted the bishop in person in Ireland, saying that Peter wanted to spend time with him.

“Casey told Arthur something like, ‘Annie was a whore who slept with the whole town.’ He said, ‘He’s not my kid,’ ” said Peter Murphy, who heard the story from Pennell before Pennell died. “Arthur decided, ‘That’s it, I’m taking you down.’ ”

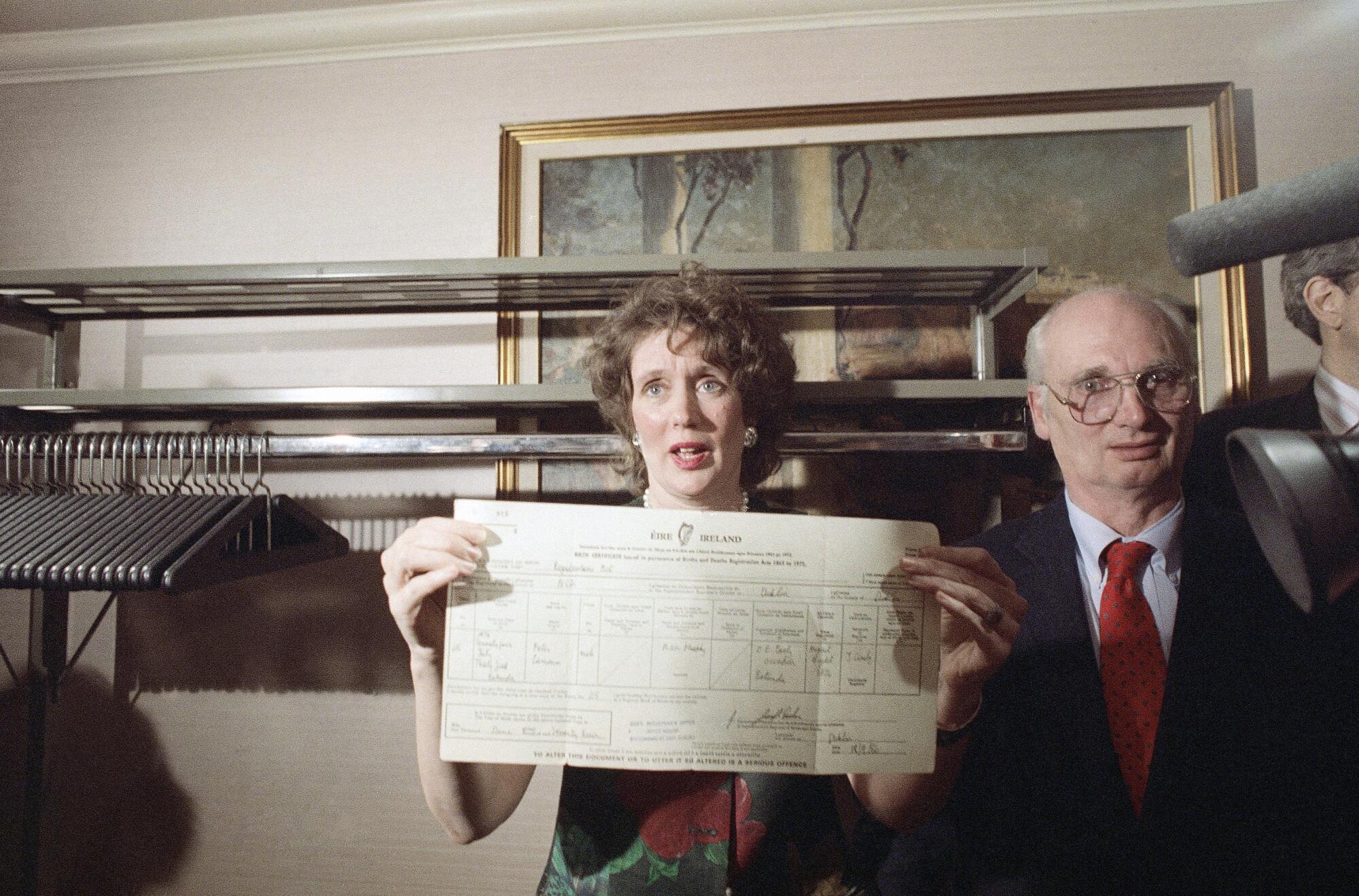

Pennell and Murphy contacted the Irish Times in 1992. It had been two years since Murphy had quietly sued Casey in New York.

The bishop, through an intermediary in the states, paid nearly $100,000 to Murphy using diocesan funds as part of the suit, but had not admitted paternity of Peter in the case, according to Conor O’Clery, a reporter for the Irish Times. That was on top of the $275 he sent each month for the first 15 years of Peter’s life.

O’Clery was dispatched to Connecticut to interview Murphy.

“It was evident the story was true. I … found her to be a slim woman of 43, attractive, composed, but full of outrage and nervous energy, and utterly convincing,” O’Clery wrote in a 2017 article.

The revelation of the bishop’s affair and son quickly spread to the front pages of newspapers across Ireland. Shortly thereafter, the Vatican announced that Casey had resigned as bishop of Galway but remained in the priesthood.

“I did what I had to do to bring him forward to his son,” Murphy said of Casey in a recent interview with The Times. “Sometimes I felt I’d play any card I had to to do it and I didn’t care. I was a little bit bitter, maybe ruthless, maybe ambitious, maybe all those things.”

Yes, she said, she felt bad for the bishop, but that didn’t deter her. “I told him … if my son comes to you and you deny him … I will do anything I have to to bring you forth. If it means tearing you to pieces, I will.”

For Irish boomers and Gen Xers, the name Annie Murphy conjures a different time. When the story broke, the country’s laws barred contraception, homosexual acts, blasphemy and, with rare exceptions, abortion.

I was a little bit bitter, maybe ruthless, maybe ambitious, maybe all those things.

— Annie Murphy

“The Catholic Church was still hugely influential in Ireland,” said Sarah-Anne Buckley, an associate professor of history at the University of Galway.

People of a certain age in Ireland remember the shocking outlines of a national scandal: the young American woman and the bishop, the hypocrisy of the clergyman, the baby born out of wedlock and without a present father, the woman’s notorious appearance on an Irish late night talk show.

“I just remember people of the generation ahead of me were literally speechless and wouldn’t have talked about it because it upset them so much. It went against everything they believed about the church,” said Cunningham, the history professor. He even recalls what he was doing when he heard about the affair: driving to Ballinamore in County Leitrim to do historical research at the county library.

“Everyone I met there that day wanted to talk about Bishop Casey,” Cunningham said. “He was bishop of Galway, but a well-known national figure.”

Murphy chronicled her affair and the subsequent cover-up in “Forbidden Fruit: The True Story of My Secret Love Affair With Ireland’s Most Powerful Bishop.” It was written with Catholic-priest-turned-author Peter de Rosa and released by Little, Brown & Co. in January 1993.

Murphy remembered landing in Ireland for her book tour that year and seeing young Irish people, many of them women, waiting for her plane. The greeting was warmer than she’d expected.

“I got off the plane and they asked me what did I do? And I said I helped take the oppressive boot of the Catholic Church off the throat of Ireland,” she said. “I said, ‘Don’t worry about me, worry about Ireland.’ ”

The rest of Ireland was not as welcoming to Murphy, an American who did not seem to fear or revere the church that held such sway on the island. As she traveled through the country, she heard people yelling crude things at her when they saw her on the street. She said she worried that someone might even try to kill her, but the name-calling proved to be the worst of it.